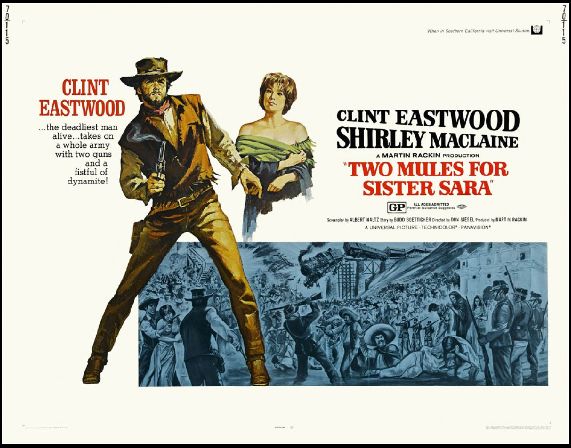

Two Mules for Sister Sara (1969 / Director: Don Siegel) was written by Bud Boetticher with the idea that he’d also be the director of the movie, but the project was taken away from him and rewritten by others as a vehicle for Clint Eastwood, who had recently risen to stardom in the Italian western. For a film that is usually called a failure, it is remarkably enjoyable, but its problems are many. What really torpedoes the movie is a ludicrous plot twist towards the end, which stops it from making much sense.

Eastwood, not wearing a poncho but still looking like the man with no name, saves a young woman from being raped by three bandits. To his surprise, the woman turns out to be a nun. They decide to go separate ways, but then they see an army regiment approaching in the distance. They’re French and they’re an occupying force: we’re in Mexico and it soon transpires that the stranger and the nun have something in common: he is a mercenary who’s in Mexico for a special assignment, she is wanted by the French for helping the revolutionaries. The two team up and finally reach the Juaristas, the Mexican resistance, and help them to slaughter an entire French regiment in an explosive finale.

The opening scene – Eastwood killing three thugs and saving a nun – seems a subtle nod to a scene in Eastwood’s first western with Sergio Leone, A Fistful of Dollars, the so-called ‘Holy Family scene’, in which he saves a young couple and their son from the terror of the film’s main villain. Directed by Don Siegel, in his own distinctive way, it also forebodes the more laconic presentation of violence which would determine some of Eastwood’s films to come, directed by either Siegel or himself, especially the Dirty Harry movies. There’s no ritual build up here, and the way in which the stranger acts is closer to Harry Callahan than No Name; the scene in which he uses dynamite to outsmart the third bandit, who uses the woman as a shield, is essential Dirty Harry: the man hesitates, then panics and runs – and the stranger shoots him in the back. The violence is almost casual, as if the stranger doesn’t really care. If people would oppose his indifference, he’d answer: and what about the nun? Who cares for her? But the stranger is no iconoclastic cop, nor is he a No Name (actually he’s got a name, Hogan): No Name would probably have saved the nun, but wouldn’t have been there in the first place. The French army on one side, the Juaristas on the other side, and he in the middle? No, too dangerous.

In Boetticher’s original script the woman was a member of the Mexican aristocracy, fleeing from the vengeance of the Mexican revolutionaries, with the American cowboy, a disillusioned Civil War veteran, escorting her to the safety of the border. It seems a typical Boetticher story about a stoic, ageing man who’s aware of the futility of his personal aspirations, seeking redemption in a humane act. At this early stage in his career, Eastwood wasn’t the right choice for the part of the disillusioned Civil War veteran who has no ties and wants none (Boetticher had written the story with Robert Mitchum in mind), so it seemed wise to change several details. It also seemed a good idea to turn it into some kind of Zapata western. However, the result of these ‘clever’ rewritings is a rather inane script: Clint is still mumbling his one-liners like No Name and although he’s been given some background, his only existentialist worries are about money and sex. Now there’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s not what the Zapata westerns were about. With the introduction of the nun, the whole affair was turned into a comedy – which probably was the best of all the changes. Considered as a Zapata western, the film is a misconception, but considered as a comedy, it often works fairly well.

The project was presented to Eastwood by Liz Taylor, on the set of Where Eagles Dare, and he decided to co-finance it because he wanted to work with her, but she withdrew and was replaced by Shirley MacLaine. She was a good second choice, a talented comedienne, very believable as a not so virtuous nun, worldly wise, unruly, but with an unswerving faith. We hear her use a very worldly vocabulary, see her taking puffs at Hogan’s cigars and swigs of his whiskey, but also see her pray and reject Hogan, who’s attracted to her and repeatedly on the brink of making a pass at her. It’s this sexual tension between a religious woman who has learned more about the world outside the monastery then the young soldier of fortune about his own heart, that fuels the narrative. It would’ve been interesting to learn a bit more about how and why she came to sympathize with the Juaristas (above all it would’ve given the film some raison d’être as a Zapata western), but then, all of a sudden, with about half an hour to go, we’re confronted with the revelation that Sara is not a nun, but a prostitute. It denies the entire movie (even Ennio Morricone’s score, which combines ironic, irreverent and solemn elements), and it’s my idea that it was some kind of afterthought, introduced to procure the film with a happy ending. But it simply doesn’t make sense. It was no more than normal that there would be sexual tension between the two people, but it was in the line of things that it was never meant to be. Their goodbye could have been a great emotional final chord. Instead we get a ridiculous final scene of the two riding off into the desert, he still mumbling his lines, she no longer dressed as a nun …

Two Mules for Sister Sara is a pleasant, if awkwardly paced movie. Even the more exciting scenes, like the blowing up of the bridge and the removal of the arrow, feel needlessly protracted. But shot in Mexico (rather than Almeria), it often looks stunning, mainly due to Mexican cinematographer (and Buñuel veteran) Gabriël Figueroa, whose lingering camera seems in love with the arid terrain. Siegel’s direction is effective, but not particularly inspired (this obviously is not his film) and during the violent finale, it becomes clear that large-scale action was not his forte. Ironically he was very fond of the finale himself. He said about it: “I had every shot tilted in the opposite direction from the one before. I worked very hard on making that battle sequence work because there was really nothing in the story that justified it. My goal was to make it justify itself by being very exciting” (see Gerald Cole and Peter Williams, Clint Eastwood – London 1983).

Two Mules for Sister Sara is a pleasant, if awkwardly paced movie. Even the more exciting scenes, like the blowing up of the bridge and the removal of the arrow, feel needlessly protracted. But shot in Mexico (rather than Almeria), it often looks stunning, mainly due to Mexican cinematographer (and Buñuel veteran) Gabriël Figueroa, whose lingering camera seems in love with the arid terrain. Siegel’s direction is effective, but not particularly inspired (this obviously is not his film) and during the violent finale, it becomes clear that large-scale action was not his forte. Ironically he was very fond of the finale himself. He said about it: “I had every shot tilted in the opposite direction from the one before. I worked very hard on making that battle sequence work because there was really nothing in the story that justified it. My goal was to make it justify itself by being very exciting” (see Gerald Cole and Peter Williams, Clint Eastwood – London 1983).

Click here to buy the BluRay re-release on Amazon.com (TBR October 16)