Every now and then we at Furious Cinema turn to one of our favorite classic genres, the western. We’ve previously posted a list of 50 Furious Westerns, and to build on that, we’re launching a series of in-depth looks at some classics of the genre. No rules. This is the third guest post in the series by Simon Gelten (one of the most active writers on The Spaghetti Western Database), make sure you also read the previous article on Shane and Rio Conchos.

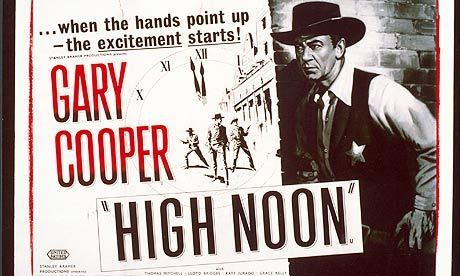

Cast: Gary Cooper (Will Kane), Grace Kelly (Amy), Lloyd Bridges (Harvey Pell, Deputy Sheriff), Katy Jurado (Helen Ramirez), Ian MacDonald (Frank Miller), Lee van Cleef (Jack Colby, man waiting for the train), Sheb Wooly (Ben Miller, man waiting for the train), Robert J. Wilke (Pierce, man waiting for the train), Lon Chaney (Martin Howe)

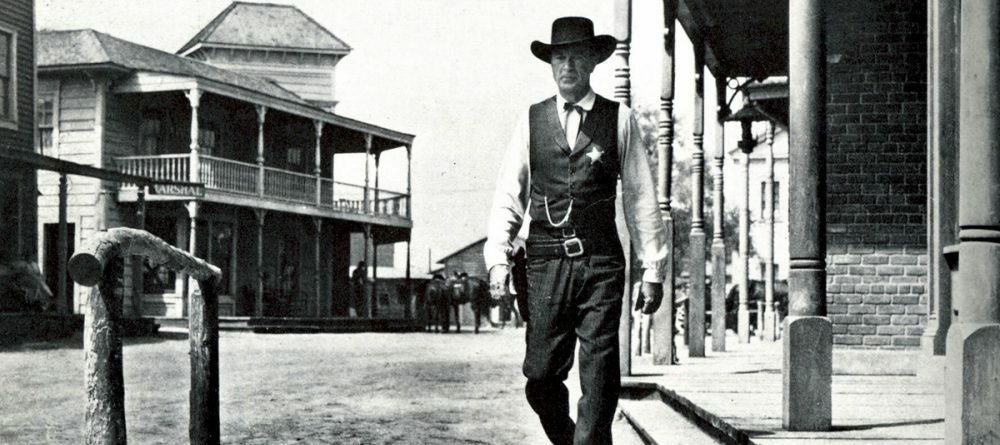

To many High Noon is the classic American western. Some of the film’s images are among the most enduring in film history: a worried but determined Gary Cooper looking through a broken window, Cooper walking down the main street, desperately looking for help, Grace Kelly shooting one of the villains threatening her husband in the back. At the same time it has met with a lot of disapproval. Some critics have accused High noon of ‘vulgar anti-populism’ and spoiling the genre with ‘social drama’.

The script of High Noon is a fusion of two classic western themes, presented with an unusual, not-so-classic twist. The first of the classic themes, is the vengeance theme, the twist is that the film’s protagonist is not the avenger, but the person the avenger is after. Will Kane (Gary Cooper), sheriff of a small western town, once put Frank Miller in jail; on his last day as sheriff, which is also his wedding day, he is informed that Miller has been released from jail, and is on his way to get even. Three of his men are waiting on the station for him to arrive. Instead of leaving the town in a hurry, Kane decides to stay, much to the regret of his Quaker wife Amy (Grace Kelly), whose religious principles condemn any use of violence, even in self defence. The second classic western theme High Noon is dealing with, is the enforcement of law and order in the western town. Like in a classic western, the town of Hadleyville is protected by its sheriff against external forces, but the townspeople are presented as a hypocritical community, faint-hearted and evasive, and we ask ourselves why on earth Will Kane would not pack his bags and call it a day.

Many of those who didn’t like High Noon, were appalled by the idea of Cooper begging for help. The idea behind this, seems to be a conception of the western as a primarily mythical genre. In it, the western hero is a man who is by definition alone, so wouldn’t ever beg for help. John Wayne and Howard Hawks even felt obliged to make an ‘answer movie’, Rio Bravo. In High Noon, Gary Cooper begs for help and gets none, so in Rio Bravo John Wayne does not ask for help, and gets some. Of course Wayne despised the movie also because he interpreted it as an allegorical attack on blacklisting, calling High Noon (in an infamous Playboy interview) ‘un-American’.

Like Don Graham has pointed out in an excellent essay on the movie, High Noon is more a movie about the community than about the individual. It’s a town western, not simply a western set in a town, but one about a town, and its people. Until High Noon townspeople had been in the background, and their main purpose was to set the skills of the hero and villain in high relief. High Noon brought them front and centre, and it wasn’t always a pretty sight (1). Still I don’t think the ‘anti-populist’ tendencies in High Noon are to be interpreted within a specific American context. There’s some evidence for this in the film itself: the judge who has married Will and Amy packs his belongings and quickly leaves town, warning Will for the upcoming reactions of the townspeople, by drawing parallels with two historical events in which townspeople cheered a returning tyrant who killed the represents of legal authority. One event goes back to the days of the ancient Romans. High Noon is a movie about a community, and it’s ‘message’ seems to be that the behaviour of communities is not exemplary, and that things have always been this way. High Noon is a more realistic western than most critics were familiar with when it was first released; it’s not realistic in the sense that it tries to represent the West in a historically correct way, but in the sense that it shows people how they are, no longer (like the more mythical westerns Wayne promoted) how they should be. Cowardice is not a specific American quality, nor is heroism. High Noon is a film that tells some things about mankind, so about us, and what we’re told, isn’t always pleasing. Most of us are like the people of Hadleyville: we wouldn’t dare to side with Will Kane, we pay a professional like Kane to do our ‘dirty jobs’ and prefer to look the other way when things become dangerous and violent.

Even those who didn’t like it, praised High Noon for the metronomic precision it was made with (2). The presence of the ticking clock, emphasizing the act that the film plays (more or less) in real time, is such a strong audio-visual metaphor that it’s hard to believe it wasn’t part of Zinneman’s original plans (according to most sources it was producer Stanley Kramer who came up with the idea). The clock has become part of the movie’s (and film history’s) folklore, just like Dimitri Tiomkin’s Score and Tex Ritter’s ballad Do not forsake me oh my darling. Whether High Noon is the best American western ever made, is a matter of personal taste. It’s wonderfully acted, especially by Cooper, and beautifully shot in black and white (avoid computer-coloured versions), the harsh black and white of Floyd Crosby’s photography symbolising the claustrophobic atmosphere and exposing every line in Cooper’s worried face. Watching High Noon today, is to discover scenes and ideas that pop up in modern westerns, from the three men waiting for the train in Once upon a time in the West to the boys enacting a shoot-out in The Wild Bunch, and the dropping of the sheriff’s star in contemporary western Dirty Harry, with Clint Eastwood as the modern day Will Kane standing up for justice in a weakened world.

Notes:

Don Graham, High Noon, in: Western Movies, edited by William T. Pilkington and Don Graham, Albuquerque, 1979.

(2) Edward Buscombe, 100 Westerns, p. 87

Buy BluRay: From Amazon.com | From Amazon.ca | From Amazon.co.uk | From Amazon.de

2 thoughts on “High Noon | 50 Furious Westerns”

That’s a great review Simon (or should that be Sherpshutter?) and I agree with every word of it although I would like to add the piece of trivia that Lee Van Cleef, who has a small part in the film as one of the hencemen waiting for Frank Miller to return, was cast by Sergio Leone in “For a few Dollars More” because Leone could remember Cleef from this film!

That’s scherpschutter allright. It’s clear that Leone loved this movie. Three men waiting for a train. And look at this final shootout, or better: the build-up to it, and this attention to details such as clocks, lines in somebody’s face.