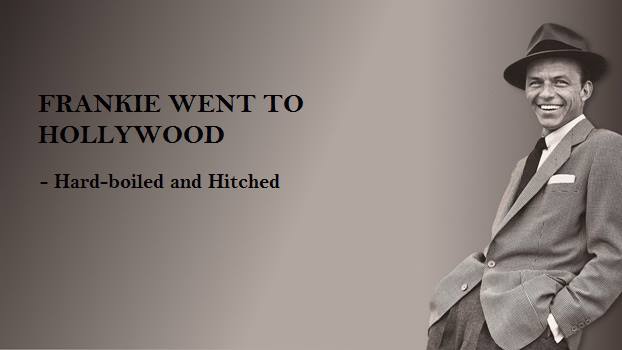

Of course we all know Frank Sinatra in the first place as a singer, but the small man with the tremendous voice was also a talented actor who appeared in more than sixty movies and won an Oscar (best performance in a supporting role) for his work on From Here to Eternity (1953). He had a natural talent for acting and director Frank Capra asked him to concentrate on acting because he thought Ol’Blue Eyes could become one of the greatest actors in history if he gave up his musical career (1). Frankie never gave up singing, but every now and then he went to Hollywood.

I – The Sinatra of the Sixties

In 1967 Frank Sinatra had very little to prove, neither to himself, nor to the world. It is often thought that the popularity of rock’n’roll had done harm to his career, but the early and mid-sixties were among the most successful periods of his artistic life. He topped the Billboard Hot 100 with Strangers in the Night (1966) and Something Stupid (1967, a duet with his daughter Nancy) and received a Grammy Award for Best Vocal performance for his album September of My Years (1965). As an actor he appeared in successful productions like Ocean’s 11 (1960), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), and Von Ryan’s Express (1965). In 1966 he was offered the role of the eponymous private investigator in the movie Harper, but he had a full agenda and hesitated so long that the production company asked Paul Newman, who eagerly accepted the role. Only twelve months later, 20th Century Fox asked him if he was interested in playing a hard-boiled detective in the movie Tony Rome. The company promised him all artistic freedom: he could pick his own director and actor.

# First interlude : Frank & Mia

When Sinatra made Tony Rome – the first part of what would become a trilogy – he was still one of the most popular entertainers on the planet, but personally he went through a crisis. In 1966 he had married the thirty years younger Mia Farrow, and only one year later the first cracks became visible in what had looked like a perfect showbiz fairy tale. But what troubled him most, was that he had become a middle-aged man and lacked the bravura and cool of some of his friends and colleagues to hide his age and worries. Some of his friends made fun of him and his young wife; Dean Martin once told him he had a bottle of whiskey that was older than Mia. On stage, Frank always looked relaxed, the coolest person on the planet, but in daily life he was a nervous and insecure. His hyperactive behavior had always been a problem (he was sent from school for rowdy behavior) and now, at the age of 52, Frankie worried about his image and looks: he feared he was no longer The Man. His personal crises would all be reflected in the three movies.

II – Tony Rome: Frank the Bogey man

The script of Tony Rome was based on a novel Marvin H. Albert called Miami Mayhem (2), about a Miami based private investigator, a former policeman living on a yacht. Rome is asked by a former colleague, now a hotel detective, to bring a young girl home who blacked out in a one of the hotel rooms. It all looks simple, but very soon he’s entangled in an intricate affair of fraud, theft and murder. Most critics thought Tony Rome was a fairly good thriller, slow-moving, but well-acted and well-written. Above all it had the right ingredients.

A good private eye in the hard-boiled tradition, is a hard-drinking, wise-cracking fellow, popular with the ladies, but still down on his luck. His cases usually look simple (locating a missing person, checking somebody’s identity or faithfulness) but they soon bring him into all kinds of trouble. As a detective he eventually wins the war after losing every battle (he’s often seriously beaten up), as a lover he wins every battle (all women fall for him) but eventually loses the war: a hard-boiled detective will be a loner forever.

Nobody had embodied the values of the hard-boiled detective better than Humphrey Bogart, who had played both Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe, the two immortal private investigators created by, respectively, Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. Bogart had always been one of Frankie’s idols, even a role model; as a young man, and rising star, he had been part of Bogey’s entourage and had started to dress and behave like him; he had also taken Bogey’s preference for Jack Daniels whiskey and his habit of wearing fedora hats.

Tony Rome showed how well Frankie had studied his role model: he played the character in Bogey style, delivering his wisecracks in a casual, yet compelling way, dominating the entire movie with his smile and hat. His strong presence contributed a great deal to the success of the movie, still Rogert Ebert thinks the movie’s only real shortcoming is Frankie’s unwillingness to play it 100% straight (3). True, some would-be funny scenes (notably one conversation about an older woman’s pussy) simply don’t fit the material. Otherwise (so for 95%) his performance is spot-on.

# Second Interlude: Frankie, Mia & the Kids

The filming of Tony Rome was a happy period in Frank’s life. It was also a very busy time: the film was shot during the day, at night he performed at the Fontainebleau Club. But the atmosphere on the set was marvellous. He knew he could be a nuisance and therefore preferred to work with people who had already proven that they could live with his quirky nature. Both director Gordon Douglas and actress Jill St. John were old acquaintances; he trusted Douglas’ craftsmanship and knew St. John from the movie Come Blow your Horn (1963). Jill was born Oppenheim and was the daughter of a rich restaurant owner and had received a first class education; she was sexy, but also had class and style. She had all the qualities Frank admired in a woman. And what’s more: she was very different from Mia.

The marriage was still intact, but Frank had started to dislike his wife’s behavior. She moved in hippie circles and he hated hippies; her provocative behavior turned him on but also revolted him. She used LSD and was addicted to pills and slimming aids. What even troubled him more was the fact that she absolutely wanted to have a child with him. Sinatra had three children (two of them older than Mia) and had the idea he had never been a good father to them. In her memoirs My Father’s Daughter, his daughter Tina describes how Frank’s children feared his mood swings. Sinatra was a manic-depressive, who had, in his own words, an over-acute capacity for sadness as well as elation (4). Today he would have been administered antidepressants, but this type of medication was still decades away.

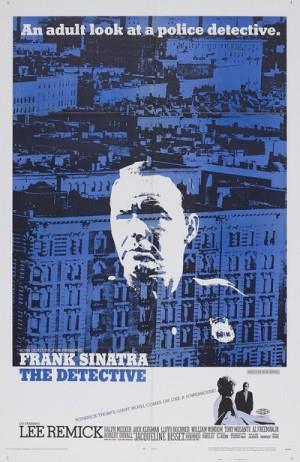

III – The Detective – the devil’s own offspring

Tony Rome was part of a Hollywood neo-noir trend, meant to revive the hard-boiled tradition (and to counter the James Bond madness). There were be no exploding lighters, nor former Nazis developing doomsday scenarios, it was all honest detective work. Other movies in this genre were Point Blank (John Boorman, 1967), Bullit (Peter Yates, 1968) and Don Siegel‘s police story Madigan (1968). When it became clear that both critics and audiences still liked these type of movies, 20th Century Fox asked for a sequel. Instead of the second Tony Rome novel, The Lady in Cement, Sinatra and his team decided to aim a little higher and adapt another novel, The Detective by Roderick Thorpe (5).

The novel (published in 1966) had received excellent reviews for its intricate, multi-layered story about a policeman turned private investigator, who’s asked by a widow to investigate the suicide of her husband. Influenced by John Le Carré’s The Spy who came in from the Cold, the novel offered a bleak, realistic look at police and detective work. Screenwriter Abby Mann (who had won an Oscar in 1961 for his work on Judgment at Nurmberg) was asked to adapt the very long novel (over 600 pages) to the screen. He turned the private eye into a police detective, and removed some of the sub-plots that were set in the distant past (World War II). The film was promoted as ‘an adult look at police work’.

Frank is detective Joe Leland, a dedicated police man investigating a brutal murder: a man has been found dead, with his penis and two of his fingers cut off. When a young homosexual suspect is brought in, Joe manages to get a confession from him and is promoted to the rank of lieutenant for having solved the case that was on every front page. The young man is sentenced to the electric chair, but the only one who is not convinced of his guilt is, of all people, Joe. A clear picture of what really happened only emerges after Joe is contacted by a young widow, who asks him to investigate the suicide of her husband.

The Detective is arguably the most ambitious movie of the trilogy. It was one of the first movies to tackle taboo subjects such as homosexuality and police brutality. Some of the scenes were meant to illustrate the marginal situation of homosexuals in society, but felt so overwrought that the whole thing nearly backfired (watched today those scenes almost look ridiculous). Most critics also felt that the flashbacks – all illustrating Joe Leland’s marital problems – were too long and slowed the already slow-moving picture further down. These scenes seemed to mirror Frank’s own marital problems with Mia; in other words: the film The Detective felt like a therapeutic session for its star.

# Third interlude: Frank, Mia and DNA

Frank had wanted to cast Mia as the widow, but in 1968 her name was on everybody’s lips and when Frank was preparing his movie, Mia signed a contract for Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s baby and refused to quit the project in favor of The Detective. Jacqueline Bisset would eventually take Mia’s place and Frank would ask her to cut off her long hair, to make her look like his wife. it was possible Frank’s last straw to save his marriage, but it was unsalvageable. He had affairs with both Jacqueline Bisset and Lee Remick (who played his wife in the movie), but apparently Mia didn’t care, didn’t care at all.

Frank had found out that the child Mia wanted from him, was in fact the only reason she had married him. It’s said that she had drawn a list of famous peoples’ names (actors, singers, politicians) she wanted to have a baby from. Her father, John Farrow, had been a film director(6) and her mother, Maureen O’Sullivan, had played Jane in a couple of Tarzan movies) and Mia was obsessed by the idea of celebrity. The TV series Peyton Place (in which she had played alongside Ryan O’Neal) had made her popular, but the marriage had made her famous. Frank offered Mia the divorce papers on the set of Rosemary’s Baby, but Mia had become more than a partner or a spouse: she dominated his life and symbolized his worst fears.

Frank hated rock ‘n roll and thought he was the world’s last save haven for people with good musical taste, but like Mia, his daughters loved Elvis and The Beatles. Nancy had appeared in the biker movie The Wild Angels (1967) and scored a smash hit on boots that were made for walking. Frank didn’t understand what was happening; he had called Elvis’ music deplorable but spent hours listening to his records, just to find out what was so special about them. Why did younger people fall for this nonsense? Frankie didn’t get it. He feared that, in spite of his enduring popularity, he was becoming a man who had outlived his time. And then the thing he had feared most happened: Mia beat him at the box-office. The Detective had done reasonably well, but not as good as Frank and his entourage had hoped for, and Rosemary’s Baby became one the top-grossing movies of the year (7).

III – Lady in Cement: Frank at the bottom of the bay

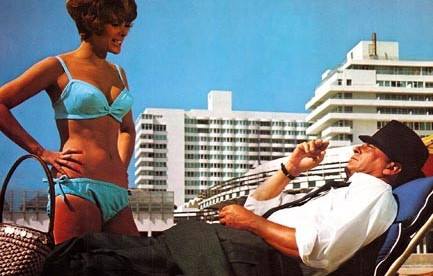

To wash away the bad taste of daily life, Frank flew back to Miami to make the Tony Rome sequel Lady in Cement. 20th century Fox had managed to snare a big bird, Raquel Welch, called by many the most beautiful woman in the world. The novel was a vast improvement over the first one and with Raquel’s body and Frank’s still considerable star power, it sounded as if it couldn’t miss, but it did.

The movie starts with a scuba-diving Tony Rome discovering a nude body at the bottom of the ocean, her feet encased in a block of cement. He’s then hired by a mysterious man – played by Dan “Hoss” Blocker, of Bonanza fame – who asks him to go searching for his missing girlfriend. The missing girlfriend is of course no other than this lady in cement. It’s always good to see a member of the Cartwright family, but the character he plays is a far cry of Chandler’s Moose Malloy (from the novel Farewell my Lovely) and doesn’t really belong in the movie. In the novel nobody’s interested in the case, but Tony decides to investigate it anyway. This is of course much closer to the true spirit of these type of stories.

However, the real problem was not Hoss, but Raquel. Frank was an advocate of the one-take approach that he had learned from Boris Karloff: if you can’t do it right in one take, you won’t be able to do it right in two or three. Frank was always sure to know his lines and hated to be called back for a second or third take. Raquel Welch was good-looking, but not a great actress and she often forgot her lines. Frank wanted to replace her (preferably by Jill St. John), but he was no longer in charge of the production: without Raquel, there would be no Lady in Cement. Frank had hoped for a good time, on and off the set, instead he had the feeling he was trapped at the bottom of the bay, his feet encased in cement.

Epilogue: Ol’ Blue Eyes is back

Lady in Cement got mixed reviews and initially failed at the box-office, but it would make some money in the drive-in circuit and with its short running-time and emphasis on leering sex and violence it turned out to be ideal stuff for late-night showings. But Frankie would only occasionally go back to Hollywood and when his concept album Watermark (1970) sold only 30.000 copies and didn’t even make the Billboard 100, his career seemed over. On June 13, 1971, on a concert in Hollywood (of all places) he announced his retirement.

Frank’s had offered Mia the divorce papers, so officially he had dumped her, but most people (including Frank himself)thought she had dumped him. According to Sinatra’s personal valet and future biographer George Jacobs, Mia had a crush on Peter Sellers during the final stages of her marriage, but Sellers turned her down and so did Leonard Bernstein. She then went to India to meet Maharishi Maresh Yogi to study transcendental meditation; her visit received worldwide media attention because of the presence of The Beatles, but it was her sister Prudence, not Mia, who attracted John Lennon’s attention (he wrote Dear Prudence for her).

Mia soon found out that life in showbiz had become far more difficult for her now she was no longer Mrs. Frank Sinatra. Rumors about her motivations to marry Sinatra had spread and many people no longer saw her as the innocent girl who had fallen into the hands of a middle-aged Casanova, but as a manipulative young women in search for famous DNA. She appeared in several movies made by respected directors, but none of them proved to be a success. It would eventually take Woody Allen, not a man famous for his glamorous way of life, to put her name back on the map.

Sinatra soon started thinking about a comeback. He had reconciled with Elvis Presley and even recorded some of the King’s hits, and in 1969, when his career was at a low point, he had recorded My Way, an English language version (by Paul Anka) of a French song by Claude François, Comme d’habitude. Reportedly he didn’t care much for it, but over the years it would become his most popular song. In 1973 he made is comeback with a television show and an album both called Ol’ Blue Eyes is Back. The album was a big success and the TV special was one of the most popular showbiz events of the year. He was still The Man. And the best was yet to come.

References:

- George Jacobs & William Stadiem, Mister S. – My Life with Frank Sinatra, Harper Collins Publishers, New York, 2003

- The Pop History Dig, John Doyle, Mia’s Metamorphosis, 2010

Notes:

- (1) Frank Sinatra biography on IMDB – http://www.imdb.com/name/

nm0000069/bio#trivia - (2) http://www.goodreads.com/book/

show/7085479-miami-mayhem - (3) Roger Ebert’s review: http://www.rogerebert.com/

reviews/tony-rome-1967 - (4) Frank Sinatra, Wikipedia page

- (5) The Detective (novel) : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

The_Detective_(novel) - (6) Farrow had dated Frank’s ex-wife Ava Gardner and it’s often said that Frank first met Mia when she was only 11 years old while paying a visit to her father. In defense of Mia some have sustained that she hardly knew who Sinatra was when she met him on the set of Von Ryan’s Express in 1965, but this is very hard to believe; Mia and her sisters often visited parties to meet celebrities and her father had a habit of introducing them to famous people; shortly before his death in 1963 he had introduced her to Salvador Dali, who was very fond of her, but saw her more as a daughter. See for instance: http://thisrecording.com/

today/2011/10/19/in-which-mia- farrow-catches-the-eye-of- frank-sinatra.html - (7) It made $33,395,426 in the US alone (and was a worldwide success) while The Detective made only $6,500,000 at home and wasn’t too successful abroad.