The Unique Worldview of Giulio Questi: Part 2 – Death Laid … What?! (click here for Part 1)

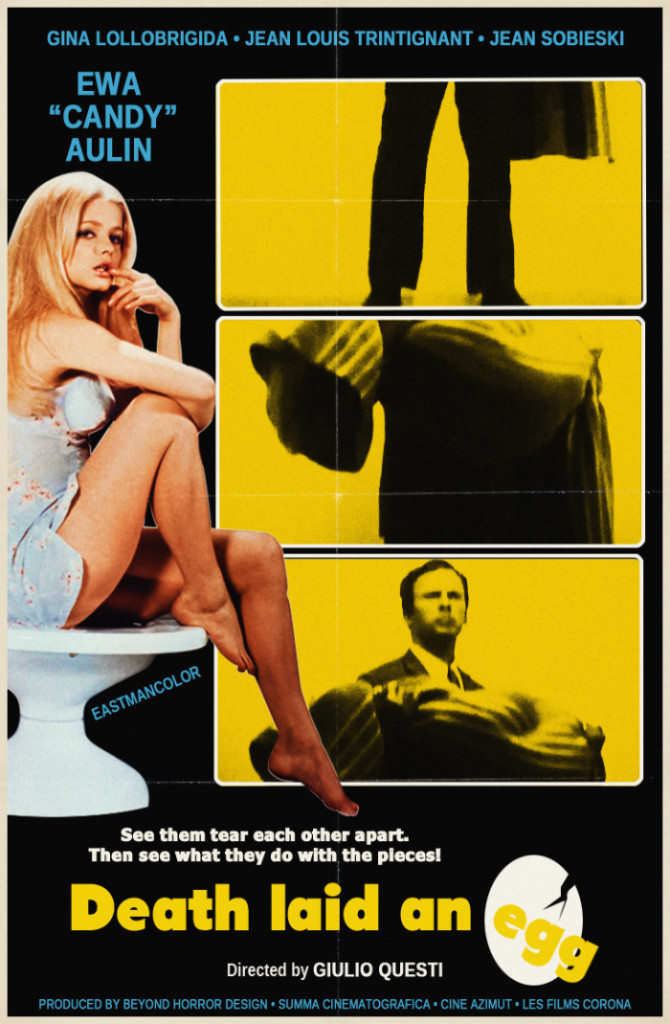

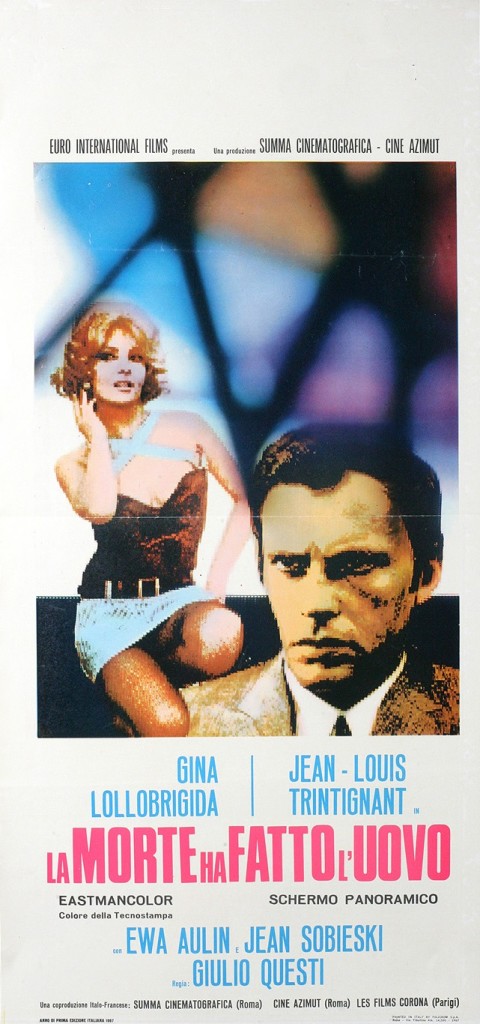

Giulio Questi’s next project was called Death Laid an Egg – the movie had been a dream of both Arcalli and Questi (in fact they had planned to do it before Django Kill), and in 1968 they were finally capable of fulfilling it. Like its predecessor, Death Laid an Egg was a surreal arthouse movie, but what differed Questi’s second film from the first one was the appearance of such names in the cast as Jean-Louis Trintignant and Gina Lollobrigida; and while Django Kill hinted at status quo ante – Italy during World War II – Death Laid an Egg was an analysis of increasing economism, offering some strong critical notes on capitalism and the effects of mechanization on the conditions of the working class. The title might be an allusion to capitalism in the sense that, according to Questi, death had laid an egg in the form of a system which humiliated the poor and abused working class people, etc. Fortunately the material does not serve the simplistic take-from-the-rich-and-give- The story starts out with an ominous murder sequence, featuring the main character – Marco – (Jean-Louis Trintignant) slitting his victim’s skin with a sharp razor. He is unaware of the fact that he is being watched by a spectator who later turns out to be Mondaini (Jean Sobieski) – a manager of the campaign popularizing products from the chicken farm owned by Marco and his wife Anna (Gina Lollobrigida). Marco and Anna are also assisted by Gabrielle (Ewa Aulin) – a distant cousin of Anna who has a secret affair with Marco. Everything seems to go on perfectly well up to the point when the realm of mystery encircling Marco’s kinky encounters with prostitutes gradually starts to crumble and Marco comes in for criticism on account of his rejection of auspicious, yet macabre genetic experiments conducted on his farm.

The story starts out with an ominous murder sequence, featuring the main character – Marco – (Jean-Louis Trintignant) slitting his victim’s skin with a sharp razor. He is unaware of the fact that he is being watched by a spectator who later turns out to be Mondaini (Jean Sobieski) – a manager of the campaign popularizing products from the chicken farm owned by Marco and his wife Anna (Gina Lollobrigida). Marco and Anna are also assisted by Gabrielle (Ewa Aulin) – a distant cousin of Anna who has a secret affair with Marco. Everything seems to go on perfectly well up to the point when the realm of mystery encircling Marco’s kinky encounters with prostitutes gradually starts to crumble and Marco comes in for criticism on account of his rejection of auspicious, yet macabre genetic experiments conducted on his farm.

Who is the Real Villain?

While violence might have been the most shocking element about Django Kill, the most perturbing ingredient in Death Laid an Egg is the fact that moral boundaries are blurred there to the extension that one is not certain who the genuine bad guy in the movie is. The motion picture inextricably endows its viewer with a sense of moral malaise – everyone watching a movie searches for a likable character and strives to identify with it, but in this case it is going to be quite an ordeal for the majority. The morally arid panorama portraying inner emotional fractures and sexual fetishes of main characters is very disquieting and causes a sensation of uneasiness.

Watching the opening scene, one deems Marco to be a villain satisfying his perverted fantasies by slaughtering prostitutes in his hotel room. The sequence is very tense, simply unpleasant to watch. There’s this presentiment that this is the bad man who will kill once again, but once Marco has left the room, he proves to be a nice guy with high ideals. He is relatively moral – even though he betrays his wife with Gabrielle, his behavior might be justified by his wife’s instrumental attitude towards other people as well as her possessiveness – besides he is repelled by genetic experiments on his poultry farm. He is likewise the sole persona whose intentions and desires are not driven by the thirst for a benefit and despite the fact that he plans to murder his wife, it is quite comprehensible since her actions are limited to increasing production, gaining more – she becomes a person who Marco scoffs at in the biggest measure. Ultimately, he emerges as a male with bleak, perverted sexual impulses (he only takes delight in pretending to butcher prostitutes), but also paradoxically enough, as a genuine human being stranded in the midst of disturbances provoked by community members aspiring to get a better social position.

By playing with genre conventions and viewers’ expectations, Death Laid an Egg attempts to shatter the composition and reconstruct it from its shards into a sinister mosaic featuring the greed and lurid impulses in contemporary capitalistic society. This approach bears some resemblance to Alain Robbe-Grillet‘s proceedings in his plotless Trans-Europ-Express (1967), in which things are even pushed further – the director talking about the movie he is working on and ceaselessly discussing turnabouts and successive points in the motion picture. Thus, it is a movie within a movie. Though Death Laid an Egg is far less avant-garde and texturally frivolous, it seems to be inspired by some aspects of Robbe-Grillet’s movie such as a sadistic protagonist (performed by Trintignant in both movies) and playing with the audience and its expectations. At the same time a game contrived by Mondaini at the party in Marco’s house brings Luis Buñuel’s El ángel exterminador to mind.

The concept wouldn’t have worked without the added value of Franco Arcallli’s razor sharp montage. Along with Nino Baragli and Ruggero Mastroianni, Arcalli was one of the finest Italian editors of the era, and he fills the screen with his uncannily rapid cuts; the symbiotic cinematography by Dario Di Palma provides the film with an even more offbeat appearance.

The Farm and the Mutant Chickens

The Farm and the Mutant Chickens

The subplots revolve around one element – i.e. the poultry farm – and this is also the central point of the tale and a key to Questi’s political and surreal danse macabre. Initially, the onset hints at a giallo, subsequently it moves towards a flick about complicated human interactions, but Giulio Questi only combines these ingredients from disparate genres, to turn his creation into something utterly different. The material is initiated with a tone of an impenetrable opaqueness and the further the movie goes on, the more its context and subtext sinks in. The recurring motif of the farm constitutes the main theme – the analysis of capitalism and economism. The machinery in the building is more perilous than one might suspect and is one of the things involved in the murky finale.

This is also the spot where the materialization of mutant chickens is executed by a scientist who works for Marco. The headless hens devoid of their plumage represent probably one of the most grotesque and distinctive of Questi’s ideas – so brazen and absurd that it ravishes with its impossibility and perfectly displays Questi’s artistic independence and swagger. In addition to this, it excellently discloses the ruthlessness of great companies which are eager to do everything in order to increase their production, even if it means to ignore ethics and the laws of nature.

Hens, People and Even More Hens

Throughout the entire movie, people are likened to chickens and vice versa. Probably the aim of this comparison is to visualize a role of a unit in modern capitalistic society which represses ambitions of an individual whose only task is to consume and to produce – just like hens crammed in their cages, whose only purpose is to deliver eggs and meat. Whilst preparing a campaign encouraging to purchase products from Marco’s farm, chickens are advertised as an engineer, a medic, a politician, a businessman and a soldier. This atypical touch perchance stems from Questi’s notions on capitalism and its approach towards a human being – the population is not significant for the system, but the profit itself which is part and parcel in the world of economics devoid of any friendly demeanor towards costumers.

On a party held by Marco and Anna, Mondaini embarks on a game according to which couples are to enter “the room of truth” deprived of all objects which could elicit memories in their relationships and free to do whatever they wish. One of the guests grows resentful and scoffs at this quirk. “You think people will act like chickens?” he inquires. Right, is it possible? Giulio Questi leaves viewers with this unresolved question which everybody has to face on his or her own.

Various Versions

While discussing Death Laid an Egg, it’s essential to keep in mind that the currently available version of the motion picture is heavily trimmed. On the day of its premiere, Death Laid An Egg was twenty minutes longer and supposedly far more bizarre, which renders it all even more puzzling and fascinating forasmuch as the flick implicates even more strange motifs. There’s no doubt that it’s more than just a rumor since Cineteca Nazionale Italiana owns this print of Death Laid an Egg and some fotobustas from the era show a surreal character played by Renato Romano who is totally non-existent in the obtainable cut (3), thus it is extremely difficult to fully analyze Questi’s second effort inasmuch as these 20 missing minutes contain a great deal of clarification which would shed even more light on this singularly outré Questi’s pic. The prevalent edition, gloated over by cinephiles is just an upshot of commercialization of Questi’s original concept, which was decidedly far more disquieting and elusive, executed on a streak of a great success of then-prosperous gialli during its second release in the seventies. Death Laid an Egg must have been very intractable to grasp hence it was better for producers to popularize the film as a murder mystery than an inscrutable, politically-charged portion of surrealism which was initially in Questi’s mind. The other reason why Death Laid an Egg was abridged might have stemmed from the fact that the material had to be adjusted to the medium of the television and a principle of obtaining an approval of showing any picture depended on its length – 90min, no more and no less (4). Anyway, nowadays, Mr Questi’s second work remains just as a curio shrouded in a mist of conundrum. One may only hope that the inaccessible version of this uncannily engaging piece of Italian cinema will surface one day and the integral cut will turn up on the shelves of movie stores in its bulk glamorousness.

While discussing Death Laid an Egg, it’s essential to keep in mind that the currently available version of the motion picture is heavily trimmed. On the day of its premiere, Death Laid An Egg was twenty minutes longer and supposedly far more bizarre, which renders it all even more puzzling and fascinating forasmuch as the flick implicates even more strange motifs. There’s no doubt that it’s more than just a rumor since Cineteca Nazionale Italiana owns this print of Death Laid an Egg and some fotobustas from the era show a surreal character played by Renato Romano who is totally non-existent in the obtainable cut (3), thus it is extremely difficult to fully analyze Questi’s second effort inasmuch as these 20 missing minutes contain a great deal of clarification which would shed even more light on this singularly outré Questi’s pic. The prevalent edition, gloated over by cinephiles is just an upshot of commercialization of Questi’s original concept, which was decidedly far more disquieting and elusive, executed on a streak of a great success of then-prosperous gialli during its second release in the seventies. Death Laid an Egg must have been very intractable to grasp hence it was better for producers to popularize the film as a murder mystery than an inscrutable, politically-charged portion of surrealism which was initially in Questi’s mind. The other reason why Death Laid an Egg was abridged might have stemmed from the fact that the material had to be adjusted to the medium of the television and a principle of obtaining an approval of showing any picture depended on its length – 90min, no more and no less (4). Anyway, nowadays, Mr Questi’s second work remains just as a curio shrouded in a mist of conundrum. One may only hope that the inaccessible version of this uncannily engaging piece of Italian cinema will surface one day and the integral cut will turn up on the shelves of movie stores in its bulk glamorousness.

Click here to read Part 1 “The early years and Django Kill…”