Every now and then we at Furious Cinema turn to one of our favorite classic genres, the western. We’ve previously posted a list of 50 Furious Westerns, and to build on that, we’re launching a series of in-depth looks at some classics of the genre. No rules. This is another guest post in the series by Simon Gelten (one of the most prolific writers on The Spaghetti Western Database), make sure you also read his previous articles.

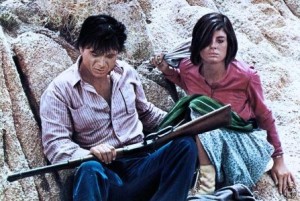

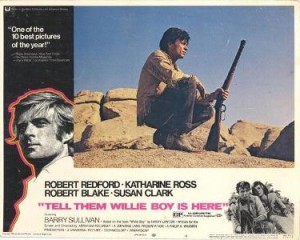

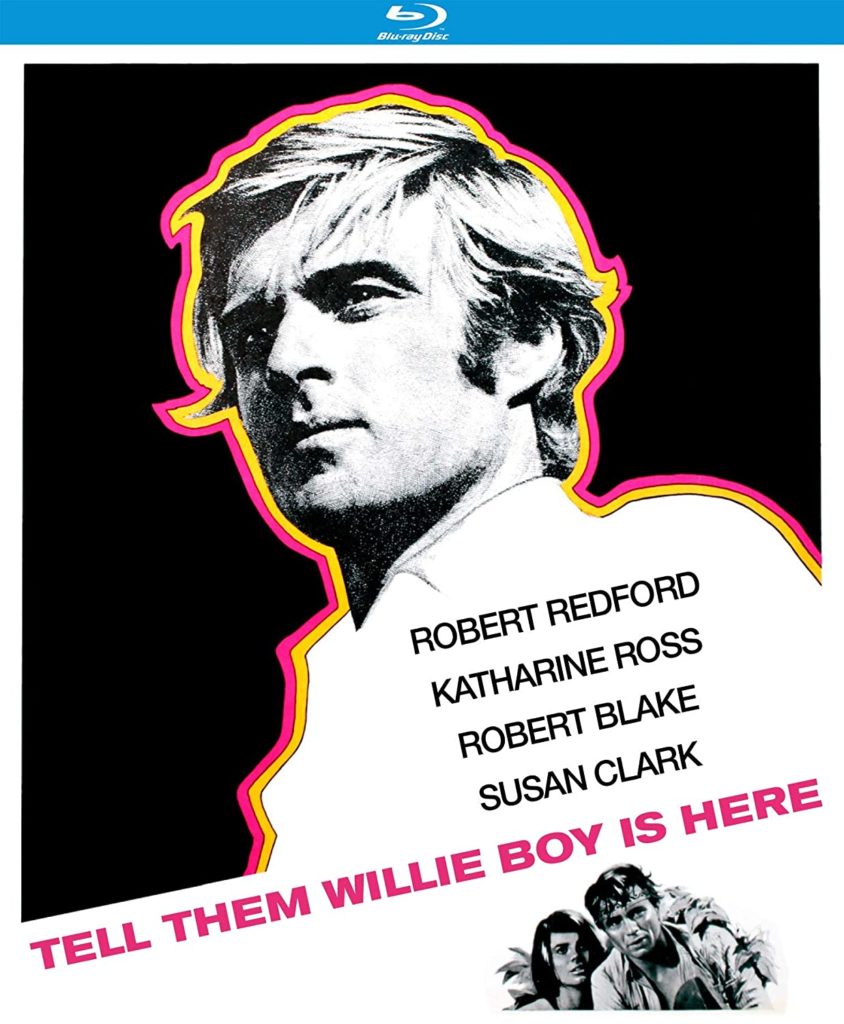

1969 – Director: Abraham Polonsky – Cast: Robert Redford (Sheriff Cooper), Katharine Ross (lola), Robert Blake (Willie Boy), Susan Clark (Dr. Elizabeth Arnold), Barry Sullivan (Ray Calvert), John Vernon (George Hacker), Charles Aidman (Judge benby), Charles McGraw (Sheriff Frank Wilson)

The second western of 1969 starring Robert Redford and Katharine Ross, after the phenomenally successful. Actually, the George Roy Hill movie, released a couple of months earlier, drew so much attention, that this movie was largely overlooked. Writer/director Abraham Polonsky had been blacklisted for more than twenty years, and his come-back movie was almost automatically labeled as counter-culture product, and therefore largely neglected by fans of western movies.

The film is based on the novel Willie Boy: A Desert Manhunt by Harry Lawton (who also co-wrote script). It tells the true story of a Paiute Indian called Willie Boy, who returns to the Indian Reservation to court a young girl, Carlota Boniface (Lola). However, the two are cousins and tribal laws don’t permit a marriage between close relatives. Willie Boy persuades Lola to elope with him, but the two are tracked down by the girl’s father, and during the ensuing skirmish, the old man is shot. According to Indian conventions, Willie Boy can now claim the girl as his wife, and the Indians from the reservation are willing to leave this as they are, but the authorities order a young sheriff to bring the young Indian back to justice.

Like many westerns from the period, Willie Boy is concerned with the passing of time and the transition from one era to another. This is illustrated by a subplot about president Taft visiting the Riverside Mission Inn in the region. Some think Polonsky wanted to draw a parallel between Willie Boy and his own situation during the blacklisting days. If so, the parallel is questionable, the conflict depicted in the movie, is cultural, not ideological. Some have suggested racial hatred was at the base of the manhunt. There’s no doubt that there were racial tensions at the time, and they may have heated up the atmosphere, but there’s no real evidence that they were at the base of things.

For a film that was described – by Pauline Kael – as ‘ideology in the saddle’, Willie Boy is remarkably reserved. All characters are rather ambiguous. Willie Boy is often rude to his girl and he’s more acting on instinct than anything else. Sheriff Cooper is reluctant to organize the hunt, but he’s not strong enough to change the situation. At one point he puts his hand in an imprint of Willie Boy’s hand in the sand, a highly symbolical scene, suggesting that both opponents are each other’s counterparts and some kind of identification had taken place. But Cooper finally washes his hands, disclaiming all responsibility, as if he were a Pontius Pilate. Elizabeth, the high class medicine woman, knows how to dress and behave in the presence of the president, but loses all her self-respect in the presence of sheriff Cooper, because she’s sexually addicted to him. The Old West is not romanticized, nor is Willie Boy shown as an obstacle to progress. He is in fact an obstacle to nothing or nobody and thinks he won’t be followed, because nobody gives a damn about what a Indian does. Of course he’s wrong. Not that people give a damn, but because the times have changed.

Some of the dialogue is a bit heavy-handed, but a great sense of doom is created, not in the least by the actors, who seemed to have grown perfectly into their characters. Katharine Ross is a bit too glamorous for the part of Lola, but she’s way better than most comments may suggest. Redford and Blake both turn in a wonderfully restrained performance, reflecting the low-key atmosphere of the narrative. Eventually, we may feel as confused as the people on-screen: If we sympathize with Willie Boy, we do so because of the hopeless situation he’s in, if we sympathize with Cooper, we do so because he’s the sheriff, but neither of the two seem to deserve our sympathy in the end. Conrad Hall’s cinematography is magnificent, and particularly effective in the dramatic finale, showing Redford and Blake as tired, worn-out people, in a sun-baked, overwhelming landscape. They finally meet face to face, but in film like this, the final showdown has no winner.

Film, fact & folklore

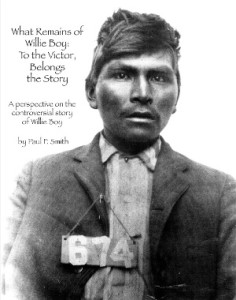

Willie has entered folklore. Today you can follow his track through the Coachella valley, were the real events took place in 1909, and pilgrimages are made to his grave. Local Indians have always claimed that Willie Boy was not caught and that he had survived; at least one history professor, Cliff Trafzer, has supported these claims. The problem with these comments, is that they want to make a hero (and an innocent victim) out of Willie Boy at all costs. No doubt the young man had met with racial prejudice, but he was a troublemaker who had been in jail (we own a mug shot with number 674 to it) and had tried to kidnap a then 13-year old Carlota before (Carlota was 15 when they eloped). There are, admittedly, quite a few unresolved questions. For instance, we don’t know how Carlota died. Was she killed by Willie Boy, or did she commit suicide (probably to hold up the posse)? Both possibilities are left open in the movie. In a recent study two scholars, James A. Sandos & Larry E. Burgess, suggest that Carlota was accidently killed by one of the members of the posse. To me this seems not unlikely. They also contest the theory that kinship was the reason for Carlota’s father to reject Willie Boy as her husband. In discussing the incident, they suggest that it might have been a religious conflict, a contest over spiritual power. Carlota’s father was a shaman, and Sandos and Burgess think Willie Boy was a Ghost Dancer. They have based this idea on circumstantial evidence, but like Linda S. Parker (of San Diego State University) has stated in a comment on the book, this theory is somewhat tenuous.

Links:

- (The West’s last Manhunt) http://www.geocaching.com/seek/cache_details.aspx?wp=GC4351&Submit6=Go

- (The Mission Inn) http://www.missioninn.com/about-the-hotel/history-of-hotel/

- (Comment on Sandos & Burgess by Linda S. Parker) http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1252&context=greatplainsresearch

Buy BluRay: From Amazon.com | From Amazon.ca | From Amazon.co.uk | From Amazon.de

2 thoughts on “Tell Them Willie Boy is Here | 50 Furious Westerns”

Great review as usual

Vitor Louçã

Nice to see this intelligent, under-appreciated western receiving intelligent analysis. Polonksy himself encouraged the link between his own enforced exile and the persecution of Willie Boy.