A little-known opera singer Betty (Cristina Marsillach) obtains an opportunity to become popular once Mara Cecova – the main star of a forthcoming performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera “Macbeth” – gets killed in a traffic accident. Upon replacing the deceased artist and being rousingly acclaimed for her appearance, she becomes elated, but when a murderous maniac begins to pester her, her success acquires a bitter taste…

“Opera stays generally distant owing to a high number of insufficient characterisation of protagonists”

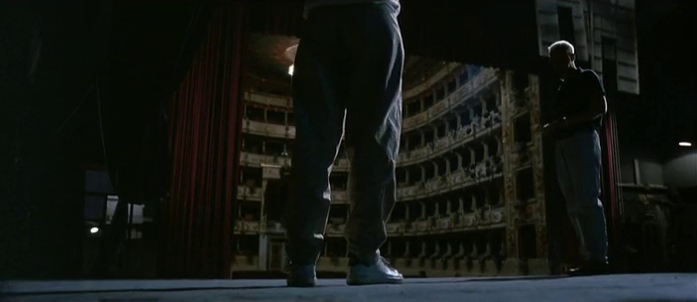

Vibrant and visually dazzling, Opera belongs to one of Dario Argento’s most famous works, but to my way of thinking, not one of his best ones. Despite the fact that the flick is aesthetically munificent and quite suspenseful, it exorbitantly submerges in its goriness and disregards its characters who remain shady, insufficient and superficial. This engenders general deficiency which is easily discernible in slower spots of this relatively enjoyable, yet somewhat flawed giallo film. The pic is initiated with a slightly ominous sequence featuring Mara Cecova growing infuriated, on being intruded by cawing ravens which are to be exploited during the performance of Verdi’s “Macbeth”. The crows promptly infuse a foreboding which is augmented even more by subsequent scenes deftly conceived by Argento. To explicate Argento’s force of framing his ideas, one might allude to the first opera sequence during which dark tints emerge as predominant and along with portentous crows fluttering around the stage, reinforce the a sense of mystery, perplexity as well as formidable beauty.

Likewise, there is a palpable sentiment of voyeurism existent in Argento’s gory and gaudy spectacle. At one point, Betty and some other singer encroach into a dressing room. Upon closing the door, the camera remains outside which implies that we contingently observe from the point of view of a bystander, perhaps the murderer. This proficiently yields a chill in the air and makes one’s blood curdle. Only when Betty hears some knocking at the door, does a viewer learn the face of the person whose eyes the audience was peering through. Ultimately, he proves to be a police inspector, who turns up in the opera so that he can investigate a mysterious murder which transpired while Betty was singing on stage, but in order to apprehend the entire situation, one has to await some time, take more notice of what is going on so as to ascertain whether it is only a tantalising gesture or de facto the bad guy. The manoeuvre perfectly exemplifies Argento’s flair of grabbing one’s attention and graciously thrusts the material onward. Furthermore, not only does Argento exhibits his capability of crafting entertaining films, but also finds some space on cinematic yarn to carry out a personal analysis of his own career just like in the case of his earlier Tenebre (1982). Mark – the man responsible for directing the opera in which Betty partakes – is a former horror filmmaker who is claimed by many to be a sadist aroused by killings taking place at the opera. This stroke indicates Argento’s reverting proclivity for inserting autobiographical constituents which are here to disprove the allegation that exposing his gloved hands as murderer’s in his flicks renders him a sadist.

Euphoric and rapturous as it may seem, the movie is unfortunately undermined by other ingredients which facilely could have been eliminated. Whilst dialogues have never been Argento’s strongest side, they appear pretty paltry throughout the whole motion picture. Aside from that, there arises a propensity for utilising monologues which one could accede to only as long as they were presented in a form of voice-over. Instead, the characters frequently utter slovenly lines, reinforcing the sense of ridiculous soliloquy which becomes even more distinct owing to amusing acting compounding the feeling of ever growing inanity. Besides, I cannot state that anything but phenomenally handled murder sequences is genuinely evocative in the latter stages of this uneven effort. All in all, Opera stays generally distant owing to a high number of insufficient characterisation of the protagonists, not to mention the subplot concerning the murderer’s identification, which I find rather inept, and the baffling denouement which seems not to be fit for Opera at all. For example, all we get to know about the character impersonated by Nicolodi is that she is the agent of the main hero. The same case is with virtually all silhouettes in Opera – they feel like incomplete models consisting of random pieces of information, which ultimately cannot cater for enough substance, merged into one big pulp.

Cristina Marsillach is fine, but the way she pronounces her lines invariably makes me smile. I do not know whether English dubbing or her acting abilities are to blame, but I have this premonition that she could have been replaced by somebody else and it would not have sapped the material. Ian Charleson, for whom it was the last theatrical movie to appear in, protrudes as the best performer in the cast. He combines a certain amount of irony and slight nonchalance as Mark. Other actors who give neat performances are Daria Nicolodi, William McNamara, but there is no escaping the fact that they just cannot exceed their marginal roles and as a corollary, they never embark on being particularly protuberant.

The cinematography by Ronnie Taylor is absolutely ravishing and constitutes the most impressive aspect of this otherwise confusing opus. As usual in case of Argento’s films, the visuals glister with their smoothness, overall buoyancy and it is truly enthralling to behold a beauteous use of stylistically lavish tracking shots, huge close-ups, innovative and swirling camera work, sumptuous lighting and even some slow-motion scenes. The music is Brian and Roger Eno, Steel Grave, Claudio Simonetti and Bill Wyman is relatively deft, but also frequently extortionately clamorous. In my view, soft-rock and opera blend does not sound very consonant, eliding my impression that these rock tracks are sometimes discordant with the action transpiring on the screen.

I am constrained to confess that I cannot recall too many flicks mingling so many good and bad factors. Opera is unique in its own way – theoretically, it implicates multiple slick concepts which are beautifully served in this grand-guignol décor. Nevertheless, despite containing many a suspenseful instant, the motion picture proves to be overflowing with too many shallow characters, lame dialogues and weak acting. Conspicuously, it is easy to disparage Dario Argento’s effort for these elements which have never been outstanding in his cinematic creations, but I believe that Opera’s shortcomings feel far more obtrusive than drawbacks of his earlier pics.

Verdict: 5/10 – not bad